VISBY MEDICAL™ PATIENT CASE STUDY

A case of undertreatment associated with syndromic management of STIs

Case Study #2: Suzanne

This study is based on a real-life case.1 Some details have been altered to fit the format of this study to preserve the identity of the patient. All photos are stock photos, used for illustrative purposes only. Posed by models.

Case Intro

Day 1 (Clinic Visit): Meet Suzanne

Suzanne, a 24-year-old young professional living in a big city, presents to a nearby clinic with recent onset urinary frequency and urgency, and vaginal discharge and irritation.

Case Update

Day 1 (Clinic Visit): Medical and Sexual History

In the exam room, the nurse collects medical and sexual history.2,3

Suzanne recounts her symptoms.

- Urinary frequency and urgency

- Vaginal discharge and irritation

- Denies any abdominal or pelvic pain

Suzanne shares that she is sexually active, but has an intrauterine device (IUD)4 and has regular menstrual periods. She does not believe she is pregnant. The nurse requests a urine sample to assess for a urinary tract infection (UTI)5 because some of Suzanne’s symptoms are consistent with a UTI, especially urinary frequency and urgency. The urine sample will also help to confirm a negative pregnancy status.5-7

Nurse-patient dialogue

Nurse: When did the urinary frequency and urgency start?

Suzanne: All my symptoms seem to have manifested around the same time – about 1 week ago.

Nurse: How would you describe the vaginal discharge and itching?

Suzanne: The discharge is more than usual and is white-ish. The itchiness is focused around the vaginal opening.

Nurse: Are you sexually active? If so, any new sexual partners?3

Suzanne: Yes, I’ve had a few relationships in the past 6-12 months, most of which turned sexual at some point. About 1 month ago, my boyfriend and I decided to be in a monogamous sexual relationship.

Nurse: You indicated that you have an IUD. Can you share what type of IUD it is?4

Suzanne: It is a copper IUD

Nurse: Do you and your partner(s) use any STI prevention methods? If so, with what frequency?3

Suzanne: Before I got the IUD, I always insisted on condoms, but now I worry less about using them. It’s rare that we use condoms now, maybe 10% of the time if I had to guess.8

Did you know?

Forms of long-acting reversible contraception (LAC), which include IUDs and contraceptive implants, are very effective in preventing pregnancy, but they do not provide protection against STIs.4,8,9

Therefore, the dual use method, which is the use of condoms in addition to an effective contraceptive (e.g. IUD), is recommended. However, dual use is not very common, especially among women using LARC.8,9

In the US, only 12% to 23% of sexually active young women (ages 18-24 years) report the use of dual methods. The use of dual methods is significantly lower among LARC users than those using other hormonal contraception (e.g. oral contraceptive pills).10

A systematic review and meta-analysis of 10 pooled studies (1990-2018) of adolescent and adult women showed that LARC users had approximately 60% lower odds of using condoms compared with those using oral contraceptive methods (odds ratio, 0.43 [95% CI, 0.30-0.63]).11

In fact, according to a US national sample of women (ages 15-44 years; 2006-2008) using LARC, only 7.3% reported dual use of methods.8

Quiz Question #1

Case Update

Day 1 (Clinic Visit): Physical, Pelvic Exam, Labs

Suzanne provides a urine sample for in-house processing. She then waits in the exam room for the physician’s assistant (PA).2

Examinations10

Physical Exam

- All vitals are within normal limits

- Patient is alert, well-developed, and well-nourished

Pelvic Exam

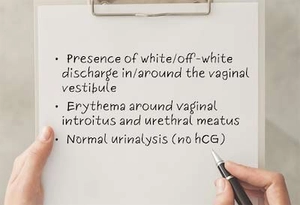

External findings:

- Noted presence of white discharge characterized as being of medium consistency and around the vaginal vestibule

- Observed erythema ail around the vaginal introitus and urethral meats, patient confirms this is the area in which the irritation is the most notable

Vaginal swab is collected for lab analysis.

Laboratory Assessments

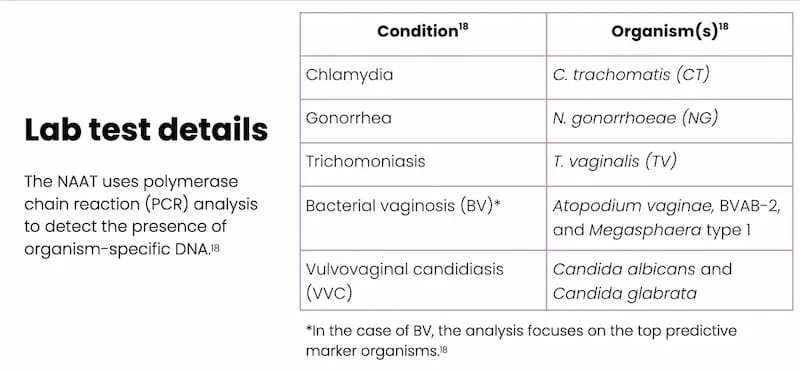

External lab assessments

- Vaginal swab is sent to an external lab for a nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) to test for the presence of organisms that cause conditions suspected in the differential diagnosis (i.e., chlamydia, gonorrhea, trichomoniasis, bacterial vaginosis [BV], and vulvovaginal candidiasis [VVC])14

In-house urine assessment15

- Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG): not detected, negative16

- Visual assessment: slightly cloudy; possible pyuria17

- Chemistry assessment: no protein, glucose, or blood detected

Quiz Question #2

Case Update

Day 1 (Clinic Visit): Treatment Plan

The PA reviews his case notes.

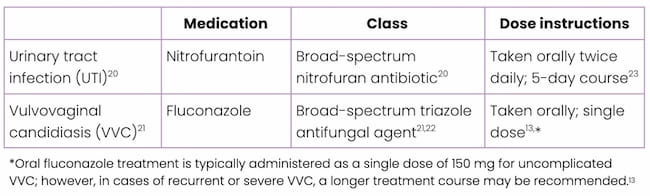

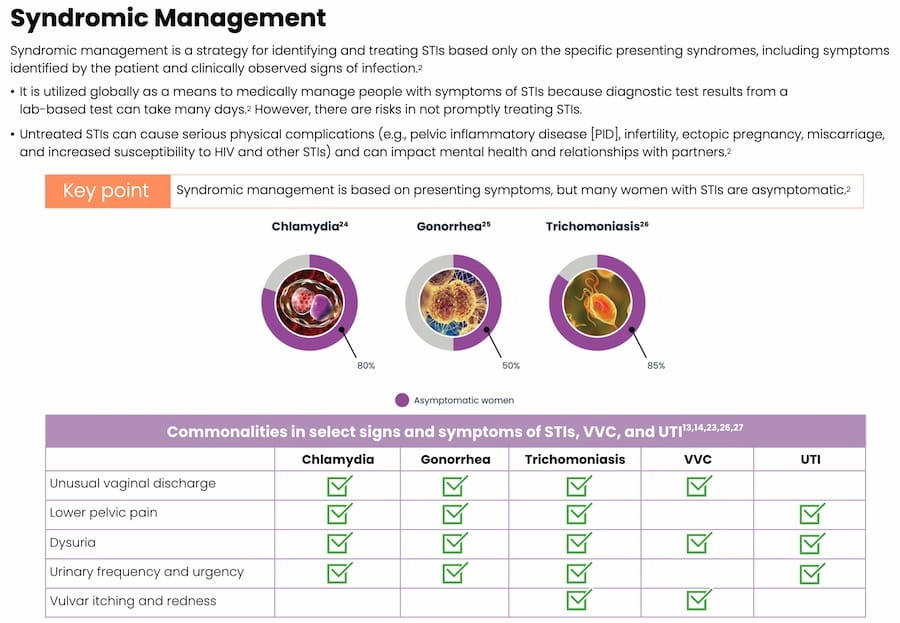

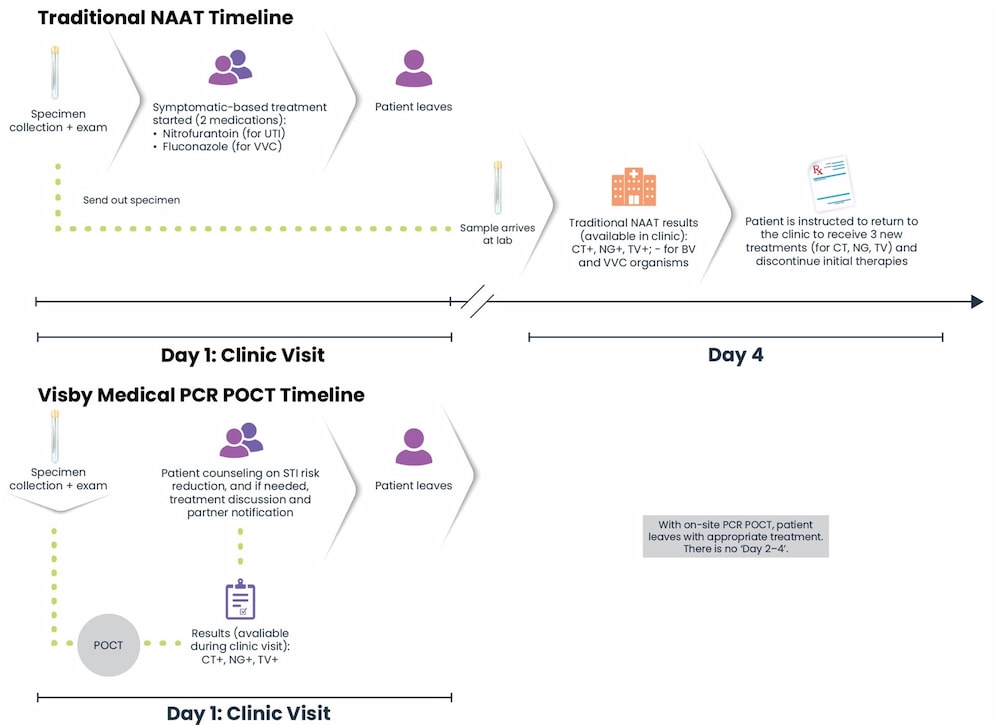

A definitive diagnosis from the lab test will likely not be available for several days, so the PA recommends empirical treatment or syndromic management targeting UTIs and VVC.2

*Oral fluconazole treatment is typically administered as a single dose of 150 mg for uncomplicated VVC; however, in cases of recurrent or severe VVC, a longer treatment course may be recommended.13

Did you know?

Urinary symptoms are associated with both UTIs and STIs, and both infections can occur concomitantly. It is estimated that about 20% of adult females with a culture-confirmed UTI also have a concomitant vaginal or cervical infection caused by an SI, including chlamydia, gonorrhea, and trichomoniasis.6

In a study of 296 sexually active females (aged 14-22 years), patients presenting with urinary symptoms in the absence of a formal UTI diagnosis, were more likely to have a trichomoniasis infection than a UTI. Additionally, 65% of patients presenting with sterile pyuria, actually had an STI, specifically trichomoniasis or gonorrhea. This makes it challenging for clinicians to determine if the origins of urinary symptoms are in fact due to a UTI or if they may be the result of an STI.6

Case Update

Day 4

The clinic receives STI lab results, which have been reviewed by the PA. The results confirm that Suzanne does not have VVC, but she does have chlamydia, gonorrhea, and trichomoniasis.

At this point, Suzanne has taken fluconazole and has had 4 days of therapy with nitrofurantoin – all without a definitive, data-driven diagnosis. Now, the clinic has to try to contact Suzanne by phone to instruct her to discontinue those treatments and return to the clinic to pick up prescriptions to treat for the 3 STIs:

- Azithromycin for chlamydia28

- Metronidazole for trichomoniasis29

- Ceftriaxone for gonorrhea, which, as an intramuscular injection, requires Suzanne to return to the clinic for administration30

Key Point

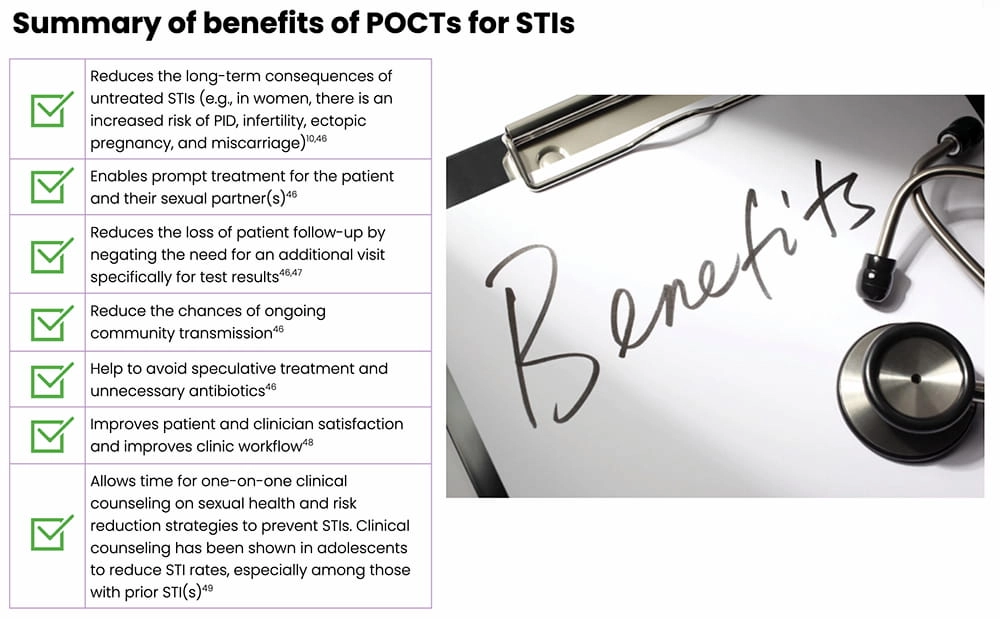

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), simple, rapid, and accurate point-of-care tests (POCTs)31 can greatly improve STI management by allowing a clinician to definitively diagnose and appropriately treat potential STIs.32

Implications of Undertreatment

Antibiotic Misuse

- Misuse of antibiotics can occur when a patient is prescribed the:35

- Wrong antibiotic (e.g., not as effective for a particular type of bacterial infection)

- Wrong dose

- Wrong duration of treatment

- According to the WHO, antibiotic resistance develops more rapidly via the misuse and/or overuse of antibiotic therapies.34

- In 2015, the WHO adopted a global action plan that summarized the current public health crisis and detailed key objectives. The objectives included increasing awareness and providing continuing education, promoting ongoing surveillance and research, supporting improved hygiene and infection protection measures, optimizing the use of currently available therapies, and expanding the global treatment armamentarium with novel therapies.34

- For example, the bacterial STI caused by N. gonorrhoeae has, over time, developed resistance to almost every antibiotic that has been used to treat it, resulting in limited effective treatment options.2,35

- Antibiotics, like all medications, come with side effects.33

- For example, nitrofurantoin, a common treatment option for UTIs, can cause side effects including nausea, vomiting, changes in facial skin color, dark-colored urine, flatulence, headache, and weight loss. It has also been associated with interstitial pneumonitis and pulmonary fibrosis, both of which are potentially fatal.20

Quiz Question #3

Case Update

What if STI Test Results Are Available During the Patient Visit?

Let’s revisit Suzanne’s story, but see how different it would play out if the clinic was equipped with a rapid, highly accurate POCT, such as the Visby Medical Sexual Health Test…

- During her clinic visit, the nurse asks Suzanne to provide a self-collected vaginal swab and urine sample; both samples are processed right away, at the start of the visit.

30 minutes later…1

- Suzanne meets with the PA, who has both her urinalysis and the POCT results.

- The POCT comes back positive for all three STIs tested – chlamydia, gonorrhea, trichomoniasis.

- The PA provides one-on-one clinical counseling on sexual health, including information on the consequences of untreated STIs and risk reduction strategies to prevent STIS.1,38

- Expedited partner therapy (EPT) is discussed as an option for Suzanne’s sexual partner(s) as a means to prevent re-infections and further transmission.39

Key Point

If this POCT had been used in the clinic, Suzanne would have promptly received the appropriate treatments for the three STIs and EPT, thereby reducing potential community spread and reducing the need for clinic follow-up.1,2

Note: Detection of organisms that cause BV and VVC are not part of the Visby Medical Sexual Health Test; an alternate diagnostic test would be needed for those two infections.

Did you know?

Clinical counseling on STIs, including information about risk reduction, contraceptives, and safe sex practices, is an effective means to reduce high-risk STI behaviors in both adolescents and adults.38

A systematic review of 13 meta-analyses (representing 248 studies) found that behavioral counseling aimed at promoting coltdom use was effective in reducing STIs, improving safe sex practices, and providing education on STIs and their prevention.38,41

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the American Academy of Family Physicians (AFP), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) all recommend routine clinical counseling around STI prevention and safe sex practices.38 However, a recent Kaiser Family Foundation study showed that this type of counseling was not routine among women aged 15 to 44 years, with only 30% of women reporting a recent conversation with a clinician about STIs.38

Visby Medical Sexual Health Test

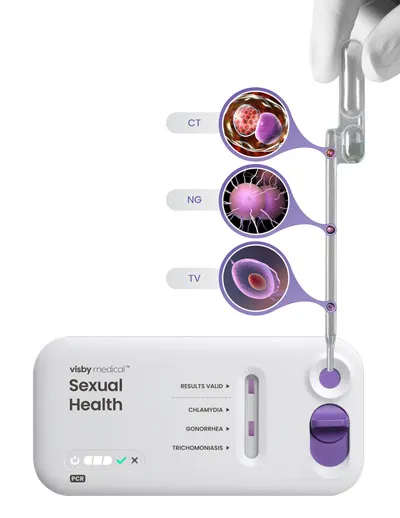

The Visby Medical Sexual Health Test46 is a POCT that enables result-driven, effective treatment delivery during a single clinic visit.

- It takes less than 30 minutes to process results from a patient-collected vaginal swab.

- It is a compact, single-use, disposable, nucleic acid amplification polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test that can test for and distinguish the genetic material of three pathogens causing chlamydia (CT), gonorrhea (NG), and trichomoniasis (TV).

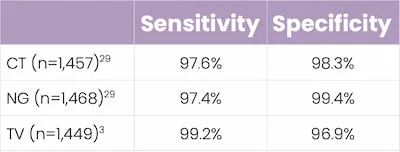

- In studies, this POCT demonstrated high percent sensitivity and specificity across all three STIs.

Key Takeaways

- Traditional PCR-based STI testing (e.g., lab-based NAATs) can take several days to return results; in this instance, syndromic management may be used to treat potential STIs.36,37

- Syndromic management of STIs can lead to both under- and overtreatment2

- Inappropriate use of antibiotics comes with risks

- Untreated STIs or failure to appropriately treat STIs increases the risk of complications, especially in women (e.g, pelvic inflammatory disease, infertility, ectopic pregnancy, miscarriage)2,44

- Point-of-Care testing allows a patient to receive an exam, precise diagnosis, and appropriate treatment all in one clinic visit42

- This helps to expedite treatment for both the patient and their sexual partner(s), and reduce community spread37,44

Traditional PCR/NAAT vs POCT44

References

- Dawkins M, Bishop L, Walker P, et al. Clinical integration of a highly accurate PCR point-of-care test can inform immediate treatment decisions for chlamydia, gonorrhea and trichomonas. Sex Trans Dis. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001586.

- Guidelines for the management of symptomatic sexually transmitted infections. World Health Organization (WHO) website. Published July 15, 2021. Accessed January 20, 2022.

- A guide to taking a sexual history. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website. Reviewed January 14, 2021.

- Long-acting reversible contraception (LARC): intrauterine device (IUD) and implant – FAQs. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) website. Updated November 2021.

- Urinary tract infections. Office on Women’s Health website. Updated November 10, 2017.

- Huppert JS, Biro F, Lan D, Mortensen JE, Reed J, Slap GB. Urinary symptoms in adolescent females: STI or UTI? J Adolesc Health. 2007;40:418–424.

- Car J. Urinary tract infections in women: diagnosis and management in primary care. BMJ Learning. 2006;332:94–97. Thompson EL, Vamos CA, Griner SB, et al.

- Sexually transmitted infection prevent with long-acting reversible contraception: factors associated with dual use. J Sex Transm Dis. 2017;44:423–427.

- Long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices – Practice Bulletin No 186. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) website. Published November 2017. Accessed January 20, 2022.

- Walsh-Buhi ER, Helmy HL. Trends in long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) use, LARC use predictors, and dual-method use among a national sample of college women. J Am Coll Health. 2018;66:225–236.

- Steiner RJ, Pampati S, Kortsmit KM, Liddon N, Swartzendruber A, Pazol K. Long-acting reversible contraception, condom use, and sexually transmitted infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2021;61:750–760.

- Sexually transmitted infections prevalence, incidence, and cost estimates in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website. Reviewed January 25, 2021.

- Workowski KA, Bachmann LH, Chan PA, et al. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2021;70:1–187.

- Syndromic management of sexually transmitted infections. Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) website. Accessed January 20, 2022.

- What is a urinalysis (also called a “urine test”)? National Kidney Foundation® website. Reviewed August 8, 2016.

- HCG in urine. Medline Plus website. Updated January 12, 2022.

- Simerville JA, Maxted WC, Pahira JJ. Urinalysis: a comprehensive review. Am Fam Physician. 2005;71:1153–1162.

- Coleman JS, Gaydos CA. Molecular diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis: an update. J Clin Microbiol. 2018;56:e00342–18.

- Tomas ME, Getman D, Donskey CJ, et al. Overdiagnosis of urinary tract infection and underdiagnosis of sexually transmitted infection in adult women presenting to an emergency department. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:2686–2692.

- Nitrofurantoin: 7 things you should know. Drugs.com website. Updated July 5, 2021.

- Fluconazole. DrugBank website. Updated January 20, 2022.

- Owens JN, Skelley JW, Kyle JA. The fungus among us: an antifungal review. US Pharmacist website. Published August 19, 2010. Accessed January 20, 2022.

- Hooton TM, Gupta K. Acute simple cystitis in women. UpToDate® website. Updated March 15, 2021.

- Markos AR. Chlamydia trachomatis genital infections. In: Markos AR, ed. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. Nova Science Publishers, Inc.; 2009:37–43.

- Lovett A, Duncan JA. Human immune responses and the natural history of Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection. Front Immunol. 2019;9:3187.

- Sobel JD, Mitchell C. Trichomoniasis. UpToDate® website. Updated July 22, 2021.

- Garcia MR, Wray AA. Sexually transmitted infections. NCBI STATPEARLS website. Updated July 15, 2021.

- Azithromycin. DrugBank website. Updated January 20, 2022.

- Metronidazole. DrugBank website. Updated January 20, 2022.

- Ceftriaxone. DrugBank website. Updated January 20, 2022.

- Caruso G, Giammanco A, Virruso R, Fasciana T. Current and future trends in the laboratory diagnosis of sexually transmitted infections. Internatl J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:1038.

- Clinic-based evaluation of point-of-care tests for the diagnosis of genital chlamydial, gonococcal and trichomonas infection in women presenting with vaginal discharge. World Health Organization (WHO) website. Published July 22, 2016. Accessed January 20, 2022.

- Antibiotics use questions and answers. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website. Reviewed October 6, 2021.

- Global action plan on antimicrobial resistance. World Health Organization (WHO) website. Published 2015. Accessed January 20, 2022.

- Bowen VB, Johnson SD, Weston EJ, Bernstein KT. Gonorrhea. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2017;4:1–10.

- Adamson PC, Loeffelholz MJ, Klausner JD. Point-of-care testing for sexually transmitted infections: a review of recent developments. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2020;144:1344–1351.

- Morris SR, Bristow CC, Wierzbicki MR, et al. Performance of a single-use, rapid, point-of-care PCR device for the detection of Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, and Trichomonas vaginalis: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21:668–676.

- Evidence summary: counseling for sexually transmitted infections. Women’s Preventative Services Initiative website. Accessed January 20, 2022.

- Expedited partner therapy. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website. Reviewed April 19, 2021.

- Partner treatment for STIs. Guttmacher Institute website. Published December 1, 2021. Accessed January 20, 2022.

- Von Sadovszky V, Draudt B, Boch S. A systematic review of reviews of behavioral interventions to promote condom use. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2014;11:107–117.

- Toskin I, Murtagh M, Peeling RW, Blondeel K, Cordero J, Kiarie J. Advancing prevention of sexually transmitted infections through point-of-care testing: target product profiles and landscape analysis. Sex Transm Infect. 2017;93:S69–S80.

- In-iw S, Braverman PK, Bates JR, Biro FM. The impact of health education counseling on rate of recurrent sexually transmitted infections in adolescents. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2015;28:481–485.

- Natoli L, Maher L, Shephard M, et al. Point-of-care testing for chlamydia and gonorrhea: implications for clinical practice. PLoS One. 2014;9:e100518.